Options Reflect Limited Downside Risk in Equities

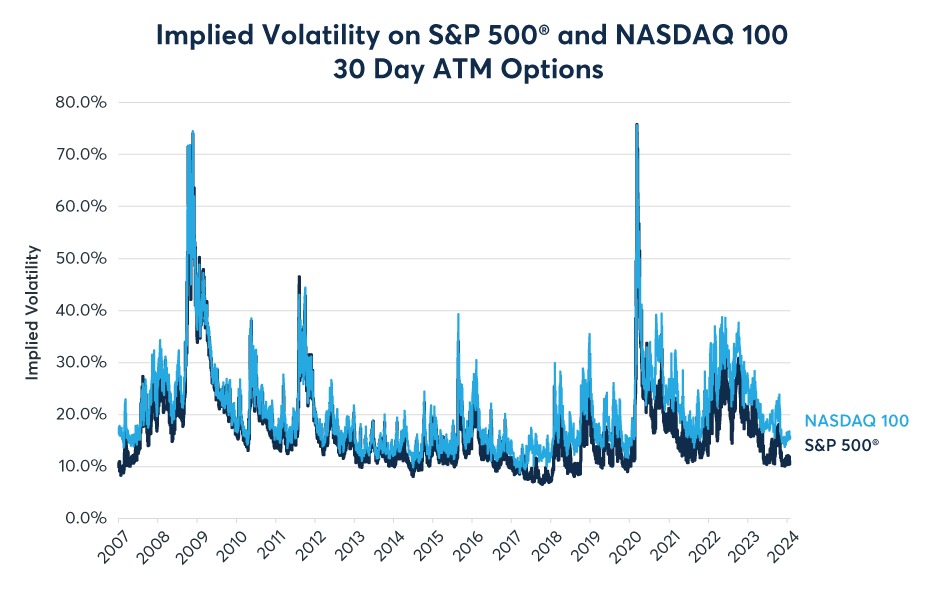

Implied volatility on S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100 at-the-money (ATM) options recently fell close to record lows (Figure 1). In some respects, this isn’t surprising as both indices have been moving up steadily, hitting their first record highs since late 2021.

Figure 1: S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100 option implied volatility near record lows

The volatility skew (also called risk reversal) for both indices is exceptionally evenly balanced with out-of-the-money put options priced only modestly higher than out-of-the-money call options (Figures 2 and 3). So, not only do traders see much lower-than-usual overall risk ahead, they are also less concerned than usual about the potential for a drastic drop in equity markets. Why are options traders being so sanguine?

Figure 2: S&P 500 put options are historically cheap compared to calls

Figure 3: Nasdaq 100 put options are historically cheap compared to calls

There are reasons to wonder if traders might be under-pricing risk in general, and especially for the possibility of downside risk in the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100. For starters, the Fed and its peers around the world have just completed the largest tightening cycle since 1981.

These rate hikes have produced a sharp inversion of the yield curve, especially in the U.S. where short-term rates are more than 100 basis points (bps) above long-term U.S. Treasury yields. This is the sharpest inversion of the U.S. yield curve in over 40 years. Yield-curve inversions in 1979, 1981, 1989, 1990-2000 and 2006-2007 preceded recessions in 1980, 1981-82, 1990-91, 2001 and 2007-2009, respectively. On average, the slope of the yield curve correlates positively with subsequent economic growth with a lead of two to two-and a-half years, with periods of steep yield curves often presaging periods of growth and inverted curves often occurring in the years ahead of an economic downturn (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Recessions often follow yield curve inversions with a lag

Figure 5: Lag between yield curve and subsequent GDP growth is often 2+ years

If the Fed’s recently completed 525 bps of tightening leads to an economic downturn in 2024 or 2025, it could have profound implications for equity markets. The S&P 500 suffered peak-to-trough declines of 27% during the 1981-82 recession, 20% during the 1990-91 recession, 50% during the “tech wreck” recession in the early 2000s and 60% during the 2007-2009 global financial crisis.

Periods of monetary policy tightening, and flat-to-inverted yield curves have historically been followed by periods of increased implied (and realized) volatility in equity markets. In 2021, our research caught the attention of Dr Anne Lundgaard Hansen at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3943982), whose academic study of the phenomenon reached the conclusion that the equity index volatility-yield curve cycle is actually the strongest indicator of economic downturns, outperforming the yield curve in insolation.

Admittedly, when one looks at the 30Y U.S. Treasury yield – 3M T-bill rate (3M30Y) curve side-by-side with the volatility index on the S&P 500, there seems to be no obvious relationship between the two (Figures 6 and 7). However, when one takes a two-year moving average of 3M30Y and a two-year moving average of S&P 500 ATM implied volatility (backfilled with the VIX Index pre-2007), one finds a strong, repeating relationship between the two that is closely tied to the economic cycle. Looking at that chart by itself, doesn’t elucidate much (Figure 8). It looks like a rather odd piece of modern art. However, when it’s broken down by year into a flow diagram, a cyclical pattern quickly emerges.

Figures 6 & 7: The relationship between implied vol & the yield curve isn’t obvious at first

Figure 8: Modern art or blue spaghetti? You decide.

Basically, the cycle can be summarized in four parts:

- Early-stage recovery: economic recoveries usually coincide with steep yield curves and elevated but falling implied volatility on index options.

- Mid-expansion: During the middle part of an economic expansion, volatility normally falls to low levels and yield curves are still quite steep. However, at some point, amid calm markets and an expanding economy, the central bank will turn its attention to the risk of inflation and begin tightening policy.

- Mid-expansion: During the middle part of an economic expansion, volatility normally falls to low levels and yield curves are still quite steep.

- Late-stage expansion: late-stage expansion is characterised by tight monetary policy and flat yield curves. Volatility often begins to transition from its exceptionally low mid-expansion state to a higher volatility environment.

- Recession: over the past 35 years, economic downturns have coincided with flat-to-inverted yield curves and high levels of volatility. Central banks typically respond to recessions by lowering rates and steepening the yield curve, and the cycle begins anew.

The first cycle took place from 1990 through 2000 (Figure 9). Following 387.5 bps of Fed hikes in 1988 and early 1989, the U.S. economy began to slow and officially entered a recession in July 1990, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER) business cycle dating. This downturn was characterized by a crisis of small banks, with hundreds of savings and loan institutions failing. Equity volatility was elevated.

Figure 9: The first implied-volatility yield-curve cycle took place during the 1990s

The Fed responded by cutting interest rates by 675 bps, which steepened the yield curve. Equity market volatility eased. By 1994, the economy was recovering, and markets were calm. The Fed raised rates by 300 bps in 1994 and early 1995. The U.S. experienced a soft landing in 1995 and 1996, and equity markets initially remained calm despite the much flatter U.S. yield curve.

However, there wasn’t a soft landing everywhere. Higher U.S. rates helped to trigger fundings crises in emerging markets. In June 1997, the Thai baht collapsed versus the U.S. dollar and the crisis quickly spread through Asia. By 1998, Russia defaulted on its debt, which sparked a run on a highly leveraged U.S. hedge fund called Long-Term Capital Management. Between 1997 and 2000, equity implied volatility steadily rose even as prices went higher.

The second cycle took place between 2000 and 2008 (Figure 10). High volatility and tight monetary policy in 1999 and 2000 eventually led to the tech wreck recession in the U.S. This downturn was primarily a collapse of business investment. The Fed lowered rates by 550 bps, steepening the yield curve. By 2003, volatility had begun to subside amid easy monetary policy and the U.S. housing sector was booming.

Figure 10: The second cycle took place from 2000 to 2008

In mid-2004, the Fed began a gradual tightening, bringing the yield curve to being flat to slightly inverted by mid-2006. In the 12 months after the end of this tightening cycle, the economy continued to grow and equity markets remained calm with implied volatility on options implying that traders saw little in the way of exceptional risks ahead. Many investors initially ignored the warning signs. In February 2007, two Bear Sterns-related mortgage funds failed. By July 2007, banks had largely stopped lending to one another. The S&P 500 didn’t hit its high until October 2007. During 2008, volatility soared with implied volatility on S&P 500 options eventually rising to above 80%.

The third cycle lasted from 2008 to 2020 (Figure 11). By the end of 2008, the Fed had cut rates to nearly zero, which steepened the yield curve. A recovery began in December 2009 which lasted until the pandemic struck in 2020. This time, it took over half a decade for volatility to subside. By December 2015, the Fed concluded that markets were sufficiently calm and that the economic recovery was solid enough to warrant a very slow series of rate hikes. By December 2018 the Fed had raised rates by 225bps, once again flattening the yield curve.

Figure 11: The most recent cycles began in 2009

The Fed began raising rates in 2022 and initially equity markets fell, but they rebounded in 2023 as inflation receded. Implied volatility, in general, has been declining and by early 2024 has hit near record lows. As of early 2024, the U.S. has the most inverted yield curve in decades and equity markets have remained calm. The history of the past 40 years suggests that tight money policy and calm markets may ultimately be incompatible and, perhaps, the most likely outcome is for a significant rise in volatility. It’s also worth pointing out that since 2007, Nasdaq 100 options (using ATM data from QuikStrike) are following a similar cycle to the S&P 500 (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Options on the Nasdaq 100 follow a similar cycle with the yield curve.

Our recent research into S&P 500 dividend futures and what they imply about the equities market being overvalued tends to reinforce concerns of the potential for exceptional market volatility ahead. A highly valued equity market might be more susceptible to declines if the Fed’s tightening ultimately results in an economic downturn.

Equity Index data

Dive into data insights from our liquid equity index markets that track leading economies for the U.S., Europe and Asia.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.