Has U.S. Already Won the Inflation Battle?

On July 12, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that headline inflation had fallen to 3.0% year-on-year (YoY) from 9.1% in June 2022. Core inflation, however, remained elevated at 4.8% YoY albeit improving a touch from 5.9% last June. What the BLS did not highlight was that core inflation was, in fact, much lower when viewed through an “experimental” data series: the harmonized core Consumer Price Index (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Harmonized core-CPI, which excludes OER, has come down to 2.3% YoY

The harmonized core Consumer Price Index, which excludes the imputed rent paid by homeowners known as Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER), shows that core inflation is only 2.3% YoY, less than half the official rate. The harmonized core CPI is based off inflation measures in the European Union which include actual rents from rental properties but does not assume that homeowners rent their own properties. In a nutshell, OER calculates an imputed rent that homeowners supposedly pay themselves (but don’t really) based on rents for nearby rental properties. The problem with OER is three-fold:

- OER is fictitious. Nobody pays themselves rent.

- OER is a huge share of core-CPI and distorts the overall rate. Actual rents (meaning payments from people who really rent properties from someone else) account for about 9% of core CPI. The OER accounts for an additional 24%.

- OER is a lagging indicator of the housing market and of overall inflation.

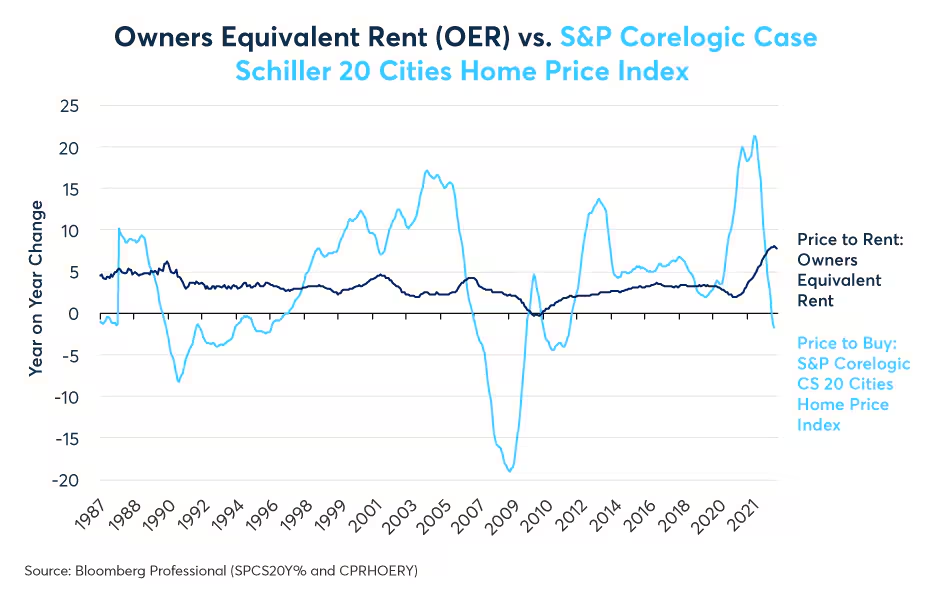

The reason why the official core-CPI is stuck at 4.8% YoY is largely because OER is rising at a pace of 7.8% YoY. But OER is a lagging indicator of housing costs. Over the past four decades, OER’s YoY changes have tended to follow the actual cost of buying a home with a lag of around 21 months, on average (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Owners’ equivalent rent is a lagging indicator of actual housing costs

Figure 3: By the harmonized core CPI measure, Fed policy is the tightest since 2007.

The pace of increase in the cost of purchasing a new home peaked in April 2022. At that time, OER was rising at only 4.8% YoY. At that point in time, the harmonized core CPI was running at around 0.5% above the official core-CPI

As of April 2023, home prices had fallen by 1.7% and yet OER was showing an 8.1% increase. Now, the harmonized core-CPI is running at 2.5% below the official core-CPI rate.

The difference between the two measures is more than an arcane, academic argument over economic statistics: it has real world consequences. The Federal Reserve (Fed), which appears set to hike rates again on July 26, is basing its rate hikes on the OER-influenced assumption that core inflation is sticky when in fact there is growing evidence that the wave of inflation has receded. When one removes the idea that homeowners pay themselves rents, the Fed may be running the risk of dramatically over-tightening monetary policy. If the Fed hikes rates on July 26 to 5.375%, the central bank will have its policy rate at more than 3% above the harmonized core-CPI measure, making it the highest real interest rate since the eve of the global financial crisis.

Bond traders are clearly worried. The 3M10Y yield curve is the most inverted it has been since the early 1980s (Figure 4) and, over the past two decades, the yield curve has been a decent indicator of future economic growth with a lag of one to two years.

Figure 4: Bond investors appear worried: the yield curve is the most inverted since 1981

One might wonder given the degree of Fed tightening as to why a recession hasn’t begun already. Part of the answer is that most debt has fixed rates, and not all debt rolls into maturity at once. For example, Fed data shows that the average weighted maturity for commercial and industrial loans is 749 days – or about two years. The average car loan extends over 66 months, or 5-1/2 years. Most U.S. mortgages are in the 15-30 year range and 92% of them are on fixed rates. The average maturity of Federal debt is around seven years. Nevertheless, as corporate and other sorts of loans roll into maturity and must be refinanced at much higher rates, the risks of defaults will grow.

Over the past 40 years, Fed tightening cycles have resulted in recessions most of the time (Figure 5). What is particularly striking about the current tightening cycle is its magnitude: the sharpest rise in Fed rates since 1981. The 1981 tightening cycle resulted in a deep economic downturn, which took unemployment to 10.8%, its worst level since the Great Depression.

Figure 5: Most Fed tightening cycles resulted in recession and this one dwarfs the others

| Monetary Policy Tightening Cycles and Subsequent Economics Downturns: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fed Rates Peaked in… | Amount of Tightening (bps) | A Recession Began in… | Lag Time in # of Months |

| May 2023? | 500 | ??? | ??? |

| Dec-18 | 225 | Feb-20 | 14 |

| Jun-06 | 425 | Dec-07 | 17 |

| May-00 | 175 | Mar-01 | 10 |

| Feb-95 | 300 | Soft Landing | N/A |

| Feb-89 | 388 | Jul-90 | 17 |

| Aug-84 | 325 | Soft Landing | N/A |

Source: Bloomberg Professional (FDTRMID), NBER Business Cycle Dating

Also of concern is that the Fed’s 500+ basis points of tightening is coming amid exceptionally high levels of debt. The level of financial leverage in the U.S. economy is double what it was in 1981 and its even higher than it was in 2007 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: U.S. debt levels are above 2007 levels and double those of the early 1980s

In short, it would be regrettable if the Fed overtightened monetary policy based on a flawed, OER-based understanding of the stickiness of core inflation. The result could be a rise in unemployment when inflation outside of the OER measure might have already come back down to pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, the fall in the price of buying homes strongly suggests that OER could begin declining sometime in 2024 and likely cause the official core-CPI measure to fall as well. Finally, if any Fed overtightening produces a downturn and if inflation outside of OER really has receded, the Fed may ultimately find itself cutting back rates much sooner than it currently expects.

Interest Rates data

Get comprehensive views of the U.S. dollar-denominated interest rate markets across the entire yield curve with our robust datasets.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.