- 2 Oct 2017

- By Erik Norland

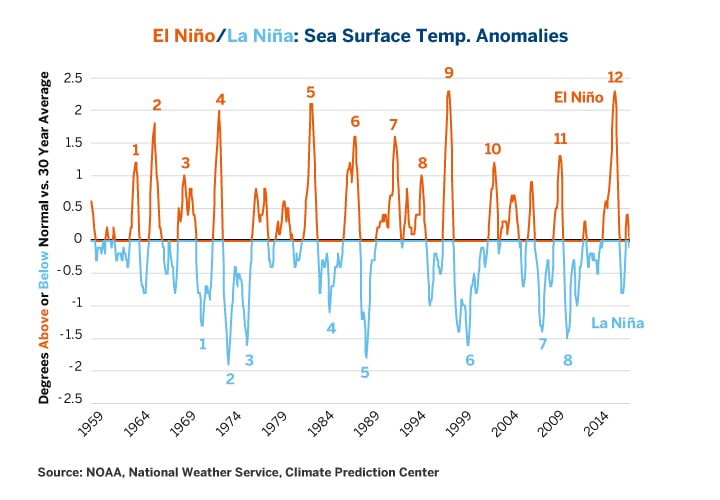

After a head fake last year, the La Niña weather phenomenon may be coming back for real this time (Figure 1). Cooler-than-normal water is pooling along the Equator on the Americas side of the Pacific Ocean (Figure 2). La Niña is associated with cooler, wetter conditions along the U.S.-Canadian border; warmer, drier conditions in much of the southern United States, and impacts weather patterns worldwide. Past La Niñas have roiled agricultural markets, sending prices on wild rides, often lower amid exceptionally high levels of volatility.

One potentially worrisome feature of agricultural markets today is that corn, wheat (Figure 3) and soy complex (Figure 4) options implied volatilities are trading at or near record lows. This might mean that markets are woefully unprepared for a potential La Niña that would bring a wave of volatility.

Since 1959, the world has experienced eight significant episodes of La Niña and 12 significant episodes of El Niño, a warming of currents. For the purposes of this paper, we consider an episode to be significant if the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) falls to or below -1°C in the case of La Niña and rises to or above +1°C in the case of El Niño.

Figure 5 shows what happened, on average, to the inflation-adjusted spot prices of agricultural products in the 12 months after the past dozen El Niños and eight La Niñas reached our significance threshold. The result is very clear: El Niño tends to be rather bullish for crop prices whereas La Niña tends to be rather bearish. Soy products (beans, oil and meal) have all tended to react more strongly to El Niños and La Niña than most of the other agricultural products traded at CME and CBOT.

It should be noted, however, that among the eight previous episodes of La Niña, there have been varying price responses from one episode to the next and from one product to another (Figure 6). This makes sense to us for several reasons. First, no two La Niñas were exactly like. Each one had a differing degree of intensity and a unique duration. Second, each La Niña had its own distinct impact on temperatures and precipitation in the world’s crop growing areas. Third, each La Niña occurred during a particular set of economic circumstances. The most recent La Niña in 2010, for instance, occurred at a time when the U.S. Federal Reserve was initiating its (near) zero rates and quantitative easing policies. Commodity prices and equities markets soared in 2009 and 2010, rallying prices of most agricultural products along with them regardless of whatever impact the La Niña might have had. Lastly, agricultural production has soared in South America since the late 1990s, which might mitigate some of the price impacts from a La Niña, which affects the Southern Hemisphere differently, with typically cooler summers in Brazil and drier winters in southern Brazil, Uruguay and northern Argentina.

To the extent that La Niñas follow on the heels of El Niños, some of the price declines that occur during the 12 months after a La Niña reaches -1°C below normal on the ONI may simply represent reversals of price increases that took place during the preceding El Niño. This should come as some comfort to those who are concerned about the possibilities of further price declines in agricultural markets. For the most part, crop prices are already at relatively low levels from several years ago.

In addition to somewhat lower average prices, the other key feature of a La Niña is exceptionally high levels of market volatility. Realized volatility during periods of La Niña has averaged about 1.5x the realized volatility level during neutral and El Niño periods for corn, soy and wheat. Here too, however, there are varying levels of volatility from one La Niña to the next. Generally speaking, the more intense the La Niña episode (the more negative the minimum reading on the ONI), the greater the degree of volatility in crop prices (Figures 7 through 11).

- Past La Niñas have tended to be bearish for crop prices but there has been a wide variety of responses from one episode to the next.

- Crop prices are already fairly depressed, so if a La Niña develops there is no guarantee that they will fall further.

- La Niña tends to correlate with exceptionally high levels of volatility in agricultural markets that far outpace realized volatility experienced during El Niños and during neutral periods, when the ONI is between -1°C and +1°C of its seasonal normal.

- Generally speaking, the stronger the La Niña the higher the degree of volatility in agricultural markets.

- Currently, options markets show an extraordinary lack of concern with respect to future price volatility.

- The rise in South American agricultural production might mitigate the impact on the price and volatility of agricultural markets.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

About the Author

Erik Norland is Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group. He is responsible for generating economic analysis on global financial markets by identifying emerging trends, evaluating economic factors and forecasting their impact on CME Group and the company’s business strategy, and upon those who trade in its various markets. He is also one of CME Group’s spokespeople on global economic, financial and geopolitical conditions.

View more reports from Erik Norland, Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group.

La Niña Protection

The La Niña weather phenomenon tends to bring high volatility and bearish sentiment to U.S. agricultural markets ranging from corn, wheat and soybeans. Investors, producers, end-users and others can manage their risk using global benchmark CME futures and options.