- 20 Jan 2021

- By Erik Norland

- Topics: Economic Events

From 2012 to 2019 the price of soybeans largely tracked the Brazilian real (BRL). When the currency’s value fell versus the U.S. dollar, so did soybean prices. That relationship, driven by Brazil’s emergence as a leading global exporter of the oilseed and the fact that the operating costs of most of the country’s farms are denominated in real, however, broke down in 2020. Soybean prices have since soared as the real weakened slightly against the U.S. dollar (USD) (Figure 1).

It’s a similar but less dramatic story for corn. Corn prices also tracked BRL, and the Russian ruble (RUB), closely for years. Those relationships, too, diverged significantly last year (Figures 2 and 3).

There appear to be three factors at play: weather, China, and energy prices. With respect to weather, a powerful La Nina has developed in the Pacific Ocean – the strongest since 2010 (Figure 4). This has coincided with a severe drought that has impacted much of South America, including key soybean and corn growing areas in Brazil and Argentina (Figure 5).

Meanwhile, China’s economy has rebounded strongly from the impact of COVID-19, with its manufacturing sector showing growth rates of 8% or more year-on-year since May (Figure 6). With China’s recovery outpacing most other countries around the world, the Chinese yuan’s value has risen by 10% against the U.S. dollar, boosting China’s purchasing power (Figure 7). With the rhetoric around the Sino-U.S. trade war seemingly on hold or winding down, China has returned to the U.S. market as a major purchaser of soybeans and other agricultural products.

Our preferred measure of China’s industrial growth, the so-called Li Keqiang index, has shown a strong correlation to the prices of soybeans, corn, wheat, and other commodities over the past 15 years (Figure 8 and appendix for more detailed information by product). For the moment, this has been quite beneficial for commodity prices, especially with China increasing its purchases of grains and oilseeds. In 2021, however, China’s economy will likely have to overcome three challenges:

- A weak export market as the world economy remains in the grip of the pandemic

- A stronger currency that might reduce the competitiveness of China’s exports

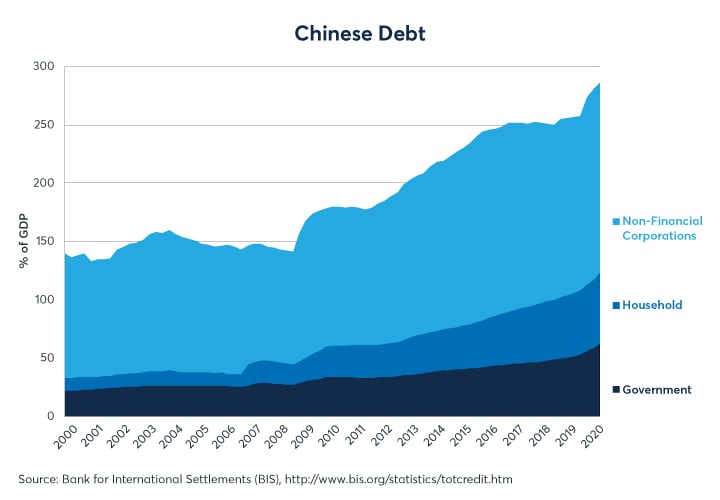

- Extremely high levels of debt, which soared during the pandemic from 250% to 280% of GDP (Figure 9).

If China’s growth was to slow in 2021 because of these or other factors, commodity prices might be impacted. When China’s economy strengthens, it also tends to benefit energy prices, given that the country is the world’s largest importer of crude oil. Crude oil prices tend to show a positive relationship with corn, soybean, and wheat prices (Figures 10-12). To that extent, the ability of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia to limit production to support the price of oil probably also benefitted the price of agricultural goods. Under ordinary circumstance, higher oil prices might have supported BRL and RUB as well, but both Brazil and Russia have been particularly hard hit by COVID-19 and disruptions related to the pandemic may have prevented their currencies from rebounding with commodity prices. That, however, didn’t stop prices for agricultural products from moving higher with crude oil.

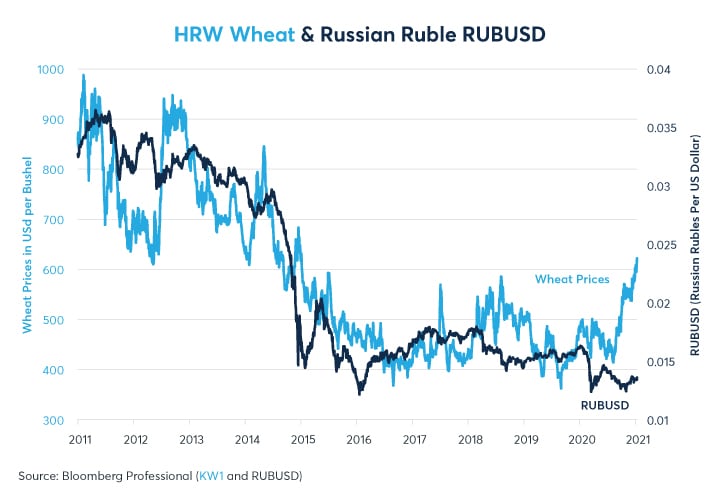

Stronger growth in China and a rise in energy prices may also have caused a divergence of the Russian ruble from the price of wheat (Figure 13). Poor crop weather in the Black Sea region may also have helped. That said, the price of wheat has tracked currencies of other wheat exporting nations such as Australia and Canada closely (Figures 14 and 15).

The key macroeconomic risk factors for prices of agricultural product in 2021 include Chinese growth, energy prices and exchange rates. On the whole, chances for a continued rally in agricultural product prices are better with sustained Chinese growth, oil prices getting continued support and weakness in the U.S. dollar. Given the rapidly evolving nature of oil demand, China’s high debt levels and challenging export environment, these factors may come into sharp focus.

- Corn, soybean and wheat prices have diverged from BRL and RUB

- Wheat prices continue to closely track AUD and CAD

- Drought in South America and inclement weather in the Black Sea region contributed to the divergence between crop prices and the currencies they normally track

- Strong demand from China may have also boosted crop prices

- Higher oil prices may have further boosted grain and oil seeds prices

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

About the Author

Erik Norland is Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group. He is responsible for generating economic analysis on global financial markets by identifying emerging trends, evaluating economic factors and forecasting their impact on CME Group and the company’s business strategy, and upon those who trade in its various markets. He is also one of CME Group’s spokespeople on global economic, financial and geopolitical conditions.

View more reports from Erik Norland, Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group.

S. American Soybean Futures

CME Group South American Soybean futures are now available for trade. Access locally-priced Soybean futures offered by CME Group and B3.