- 9 May 2017

- By Erik Norland

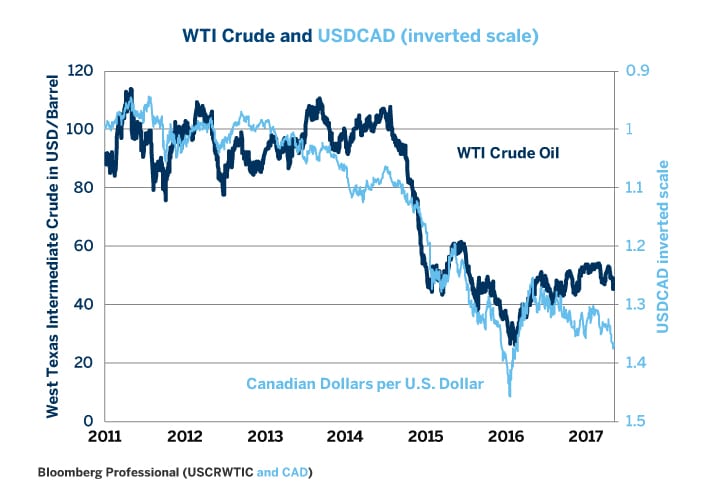

For most of the past six years, the Canadian dollar (CAD) closely tracked movements in West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil. But from mid-2016, CAD began diverging, underperforming WTI significantly (Figure 1). And the parting of ways was not the result of a generally stronger U.S. dollar (USD). The Russian ruble, which also correlates highly with oil prices, has outperformed WTI over the same period (Figure 2). Both Canada and Russia are major producers of crude oil. CAD’s divergence from oil may have to do with deeper economic problems: the country’s extremely high levels of debt and overvalued real estate prices.

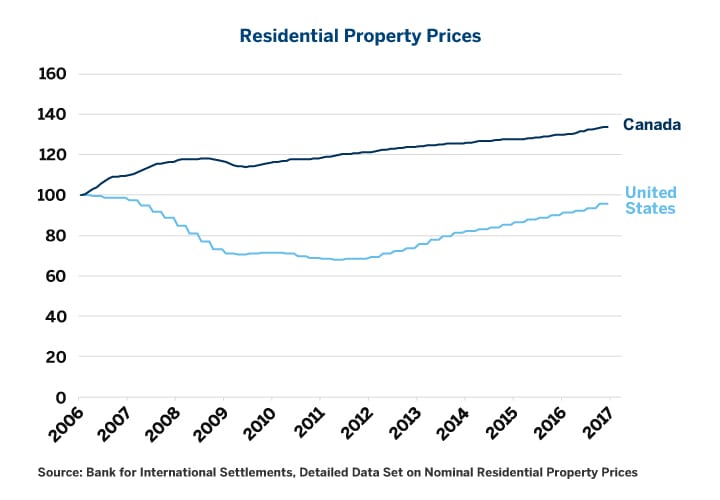

From 2007 to 2009, the United States underwent a period of reckoning as the real estate bubble popped, banks failed and unemployment soared from 4.4% to 10%. North of the U.S. border, Canadians suffered as well but to a much lesser extent. Unemployment rose, but only by half as much as in the United States. (Figure 3) and real estate prices never collapsed (Figure 4).

From the peak in 2006, U.S. real estate prices fell 30% before rebounding. Still, U.S. residential real estate prices remain a few percent below their peak. By contrast, Canadian real estate prices are more than 30% higher today than they were in 2006 and certain property markets in Canada, notably in Toronto, may be experiencing significant real estate bubbles.

How did Canada avoid the worst of the 2008-2009 recession? There are four major reasons:

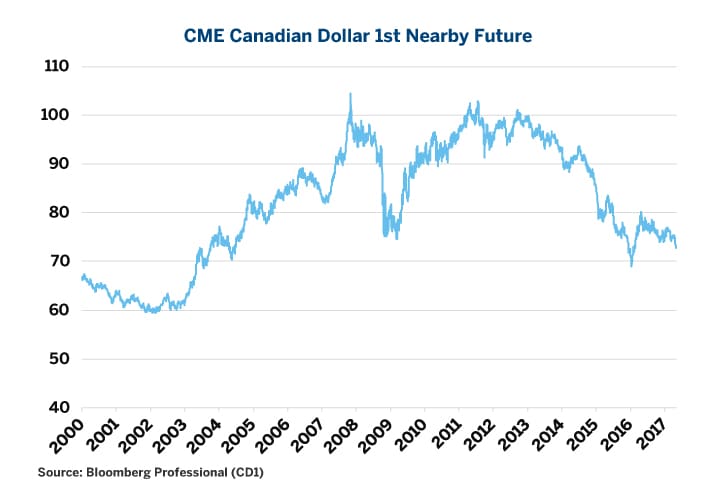

- The Canadian dollar fell sharply versus the U.S. dollar in 2008 and 2009, protecting Canada’s domestic markets from imports and boosting the country’s exports (Figure 5).

- The Bank of Canada cut interest rates almost as quickly and deeply as the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) (Figure 6).

3. In 2008, Canada was the least leveraged of the Group of Seven (G7) economies, with lower total debt levels (public + private) than the eurozone, United Kingdom or United States. Beginning in 2008, Canada’s private sector used the Bank of Canada’s low interest credit policies to increase borrowings, muting the impact of the economic downturn and returning Canada to growth (Figure 7).

4. Commodity prices rebounded sharply from 2009 through 2011, boosting the value of Canadian energy, agricultural and metals exports.

Many of the factors that helped Canada to avoid a downturn as deep as the one in the United States in 2008 and 2009 have since come back to haunt the country.

- Bank of Canada’s rate cuts encouraged a borrowing binge by the private sector that has left Canada with total debt levels exceeding that of the eurozone, United Kingdom and United States. This should weigh on Canada’s growth rate going forward and increase the likelihood of a banking crisis if real estate prices ever begin to fall. Moreover, extremely high levels of debt may necessitate the Bank of Canada to lower interest rates for longer than even the Bank of England, European Central Bank and Fed. Indeed, while the Fed has now tightened policy three times since December 2015, the Bank of Canada has kept rates at 0.5% after two rate cuts in 2015.

- Commodity prices have fallen sharply from their peaks. Oil and wheat prices are down by half and gold is down by a third. This has stalled Canada’s exports despite a weaker currency.

Canada can delay its day of reckoning by keeping interest rates low and allowing the debt level to rise further but this will ultimately result in bigger problems. A weaker CAD could also help to mask Canada’s deeper economic problems by stimulating export growth and inflation, both of which will help to keep debt ratios in check. A sudden rebound in CAD, however, could prove both toxic to Canada’s economy and therefore would probably be short-lived.

There are some bright spots in Canada. Public sector debt in Canada is quite reasonable: only 73% of GDP. This compares favorably to the eurozone’s average of 90%, U.K.’s 89% and the United States’ 103%.

The bad news for Canada is that while the private sector in the United States and Europe deleveraged somewhat after 2008, Canada’s private sector has chalked up borrowing to its gills (Figure 8). Household debt in Canada amounts to 101% of GDP, well above the 88% in the U.K., 79% in the United States and 59% in the eurozone. Likewise, non-financial corporate debt in Canada also dwarfs that of its peers at 119% of GDP compared to 104% for the eurozone, 77% for the U.K. and 73% for in the United States. None of this bodes well for Canada’s economy or currency going forward.

Bottom Line:

- CAD will remain strongly influenced by WTI price movements.

- CAD’s recent underperformance to WTI is probably due to concerns over the country’s massive levels of private sector debt and the implications for future economic growth and monetary policy.

- High debt levels may relegate Canada to slow growth and low interest rates, compared to the eurozone, U.K. and U.S.

- CAD could retest or even break its all-time low versus USD in coming years, especially if oil prices retest their 2016 lows.

- Canada might begin to run larger and larger budget deficits to support deleveraging by the private sector as happened in Japan, U.S. and Europe.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

About the Author

Erik Norland is Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group. He is responsible for generating economic analysis on global financial markets by identifying emerging trends, evaluating economic factors and forecasting their impact on CME Group and the company’s business strategy, and upon those who trade in its various markets. He is also one of CME Group’s spokespeople on global economic, financial and geopolitical conditions.

View more reports from Erik Norland, Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group.